DORA JONES - PART 2

On the evening of Tuesday, February 25, 1947, US Marshalls in San Diego California arrived at a modest colonial-style home located at 911 A Avenue in Coronado. The newly built house was owned by a couple who had recently moved to California from Boston to retire. Coronado is a small resort community in San Diego Bay, perhaps best known as the location of the historic

Hotel del Coronado. Federal authorities were called to the house to serve an arrest warrant on Mr. and Mrs. Alfred W. Ingalls on the charges of "

...involuntary servitude and slavery." Also detained that night as a material witness was their maid, Dora L. Jones.

֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎֎

Situated on a small rise on the Northside of Bean Point in

Sorrento, a small white house faces out toward Sullivan Harbor in the distance. The modest house has a porch along the front section and

an addition in the back that includes extra sleeping quarters connected by a boardwalk. The current owner tells me that the house was originally part

of a motel in Lamoine which was later moved and reassembled on the property. The members of this large family have spent more than fifty years watching sailboat races off Bean Island and enjoying sunsets from their cozy front porch.

In the days before the postal service required street signs and numbers, Summer cottages in

towns like Sorrento were simply identified by the names given by their owners.

The owner relates that when they purchased their house, the previous owners referred to it as

The Anchorage, presumably

because of an abandoned boat anchor that sat in the front yard and its location across the street from what remains

of an older dock.

However, they

found that name was sometimes unrecognized in

town

and were surprised to learn that another pejorative nickname –

Slave Quarters – was

more readily known.

That troubling moniker did not fit with the Sorrento I knew. In looking back over Sorrento's history, it seemed an especially odd name given that the resort was not developed until the mid-1880s, more than twenty years after the Emancipation Proclamation. I had previously been intrigued by a story Sturge Haskins related

to me before he died, however, his tale centered around the former

owners of Blueberry Lodge and not this other house. He reminded me that Catherine O’Clair Herson’s history, Sorrento – A Well-Kept Secret, had referred to that couple as being remembered for keeping “…a slave girl.”

Because the Slave Quarters name is reminiscent of a time

before Sorrento was founded and not something typically associated with this part of New

England, I started to piece together land records and other sources to see if I could learn a bit more about the history of the two houses. Although the Slave Quarters nickname has now faded into the past, it is important for us to acknowledge not only that it was once commonly used but why. As with other Sorrento history, I

am sure there are others with additional insights or relevant information and I

hope to hear those accounts.

What I found in my research was a common link between the two houses, a link that likely provides the answer to why the name Slave Quarters was once used. While I have not been able to establish when or who first associated the name with the cottage, perhaps this history will provide some context for us to understand the source of the nickname. But even more important than remembering why such a derogatory name was used to identify the house is what I learned about the woman central to this story. Dora Jones is the name of the African-American woman who spent ten summers living and laboring in Sorrento without compensation, and it is her history that we need to recognize, honor, and not forget.

Learning about her life also made me reflect on the many nameless people of all races, who worked endless hours while others were on vacation. While Sorrento in the early days was

certainly more rustic than Bar Harbor, there were no doubt countless domestic

servants employed in the large cottages and at the hotel. While the names of many of Sorrento’s Summer

visitors are well-known, and the memories of many local residents who worked

for Summer families have been preserved, the names of these other hard-working individuals are lost

to history. Unlike their employers, for the servants who accompanied families from their Winter homes, Sorrento was not a place they visited to relax and enjoy summertime pursuits.

Before getting to the incredible and unsettling story of the woman who provided some with the impetus to name the cottage Slave Quarters, let me trace the home’s ownership through the Hancock County Deed records. The current deed dates to 1968 and is comprised of four sections of land. The first section contains the contiguous

lots (17, 18, 19, 20 & 21 in Section L), where The Anchorage (aka Slave Quarters) was built, bordering Beech Street. The second was a piece of land across Bayview

Ave., and the third and fourth were two additional lots (15 & 16 in Section

L) adjacent to the house, (see HCD book 1165 / page 708 &and book 1067 / page 395).

On the second section, a strip of land across

Bayview Ave., there is a small deck and access to the beach. It is identified in the deed as adjacent to lot

20 in Section OO. This larger section,

originally known as the Back Wharf, was the location where supplies for the Hotel Sorrento

and the rest of the resort were delivered. Serving as the development’s backdoor, this land also housed an electric light plant, ice house, carpenter shop, and coal storage. When the hotel was sold in 1905 by the executors

of Frank Jones’s estate to Walter F. Bicknell, (the hotel would burn to the ground

shortly thereafter), these outbuildings and property were included in the hotel

deal, (see HCD book 429 / page 110). The

nickname The Anchorage is probably apt given the house’s location adjacent to

the old Back Wharf.

Prior to 1968, Powel Mills Dawley (1907-1985) and his wife Dorothy W. Dawley owned the house and land for a short period. It was the Dawleys who constructed the extra room in the rear and who passed along the name of the house – The Anchorage. Larry Lewis in his 1973 book Torna a Sorrento includes a bit about the history of the house. He relates that the Dawleys “...worked wonders...” with the house and he remembers seeing “…the tourist camps being hauled off Mrs. Hughson’s land to be joined to the rear.” Larry Lewis also confirms that the name Slave Quarters was formerly used to identify the house.

Dawley was an Episcopal minister and professor at GeneralTheological Seminary in NYC. Before

joining the seminary in 1945, Dawley was the dean of St. Luke’s Cathedral in

Portland, Maine. Rev. Dawley had served

as a summer minister at Sorrento's Church of the Redeemer for several years, during the time he was the Bishop in Portland. He and his wife may have bought the house when he moved on from that role and no longer had access to the summer rectory.

The Dawleys purchased the house and land in 1963 (see HCD Book 940 / page 59 & 981 / 286). I surmise that the Dawleys sold the house

after owning it for just five years to raise funds to buy their retirement

home, likely in Brunswick, ME where Rev. Dawley died twenty years later. It would have been during this short period between 1963 and 1968 that

the Dawleys made renovations to add space on the rear of the

house and connect it to the main unit with a boardwalk.

The house had been sold to the Dawleys by Marguerite Calendar Hunt

Ridgely (1891-1985), and that purchase included “all buildings” as well as “…

all the furniture, furnishings and other personal property contained….” in the

buildings.

Marguerite Ridgely was the widow of Julian W. Ridgely Jr.

(1887-1939) and the niece of Edward Morrell.

The Ridgely's lived in Baltimore where Julian had been a prominent lawyer

and a member of the family that built the Hampton Mansion and plantation north

of Baltimore in the 18th Century.

The connection of Marguerite Hunt Ridgely as the niece of congressman Edward Morrell provides another unrelated but significant part of Sorrento's history. Col. Edward Morrell

(1863-1917) was married to Louise Bouvier Drexel, the daughter of Francis Drexel an influential Philadelphia financier.

Morrell owned a large estate in Bar Harbor (Thirlstane) and

established Robin Hood Park where an annual horse show was held; grounds that

now house Jackson Labs. Morrell also

bought Calf Island in 1911. His wife, Louise Drexel Morrell was a devout Catholic and funded numerous

charities, including a Catholic church, school, and

a public library in Bar Harbor. She is

best known, however, as the sister of Mother Katharine Drexel, the second saint

born in America, canonized in 2000 by Pope John Paul II. Together the sisters made numerous gifts from

their inheritances to support educational institutions for

African-American and Native American children The pair also devoted time and resources to other projects and committees in support of racial justice. One of the better-known educational institutions the Drexel sisters endowed was Xavier University of Louisiana, the only historically black

Roman Catholic institution of higher education in the United States.

|

| Louise Drexel Morrell and Sister Katharine Drexel |

After the untimely death of her husband Col. Morrell at the age of 54 in

1917, Mrs. Morrell -- despite her wealth and a large estate in Bar Harbor -- evidently preferred the simplicity

of Calf Island and often stayed on the island

when visiting Maine in the summer.

Upon her death in 1945, Louise Morrell gave Calf Island to

her devoted secretary A. Leona Colby along with $3,000 to build a camp there.

Also included in Louise Morrell’s estate, were several pieces

of land and houses in Sorrento which she bequeathed to her niece, Marguerite

Ridgely. These included Sunrise

Cottage on Waukeag Ave. just past the library. Lore has it, that Mrs. Morrell

maintained this cottage to house a Catholic

priest who would travel each day during the Summer to conduct mass in her small chapel on

Calf Island.

Mrs. Morrell also owned the house originally built by W. H.

Lawrence, the manager of the Sorrento Land Company before 1900. This yellow cottage on Waukeag Ave. still stands

just past the Sorrento Library, and is today owned by Mrs. Ridgley’s great-granddaughter (see HCD book 1699 / page 364) which she inherited

from her mother, Margaret Ridgely Keith. Given the close relationship between the Drexel sisters, it is likely that Mother Katharine Drexel also spent time in Maine when she

returned from her trips around the country to the numerous missions and schools

they established. Mother

Drexel may even have also stayed in Sorrento in one of her sister’s cottages or on

Calf Island during these summer visits.

It was not until 1948, a few years after her Aunt Louise’s death,

that Marguerite Ridgley purchased the small white house which she later sold to Rev. Dawley. Marguerite probably bought this property to

accompany her other adjacent homes just down the block.

Like her Aunt, she enjoyed the simplicity of Sorrento and she may have needed the extra house for visits from her children, or for

the now elderly Mother Katharine Drexel.

It is also possible that other nuns from the Sisters of the Blessed

Sacrament or priests from the local parish were also invited to Sorrento to use

this house. However, there is absolutely no indication that the name Slave Quarters originated

during the time Mrs. Ridgely’s owned the house between 1948 and 1963 or later during Rev. Dawley's possession.

Going back further, a 1948 deed indicates that Marguerite Ridgely purchased the

land where the house stands, together with “all buildings” and

“appurtenances thereof”, from Alfred W. and M. Elizabeth Ingalls of Lynn

Massachusetts (see HCD book 723 / page 222). This deed makes clear that at the time Ridgely bought the land

in 1948 a structure already existed on the land.

More important, it is from the Ingalls’ ownership of the

land that we can make a direct connection to the Slave Quarters nickname. When Catherine Herson referred to the Sorrento

couple famous for keeping “…a slave girl,”

she was writing about the Ingalls and the national

headlines that accompanied their disturbing case.

The Ingalls Sorrento story in the Hancock County deed

records begins in the spring of 1935.* Alfred

Wesley Ingalls was a prominent Massachusetts lawyer and former state legislator. He and his wife M. (Mira) Elizabeth Kimball

Ingalls purchased

Blueberry Lodge from

Francis Lamont Robbins in June of 1935

(see HCD book 647 / page 521).

Confusingly, Mrs. Ingalls was known by different names during her lifetime -- Mira, Elizabeth, and the nickname Bessie -- so I will simply refer to her as Bessie. Blueberry

Lodge was one of the original cottages built in the new Sorrento development in 1887. Designed and constructed by Boston architect Frank Hill Smith, the cottage was first purchased by Daniel Lamont in 1888 and was enjoyed by the Lamont family for nearly fifty years.

*Note: The Ingalls name goes back much further in Sullivan's history. Ingalls Island off Weir Haven Farm is named

for the Ingalls family who once owned land on Waukeag Neck. Samuel Ingalls owned 187 acres opposite

Ingalls Island on the west side of the peninsula while his brother William Ingalls

owned 100 acres on the east side. Whether Alfred Ingalls was related to this family is

unknown and needs more research.

And yet another aside, it may instead be possible that Alfred Ingalls

was related to Charles S. Ingalls, who bought lots 24, 25, 26, and 27 in Section

A of Division 1 in Sorrento in 1887, (see HCD book 218 / page 503), located on

the harbor, approximately where Moss Harbor sits today. This deed lists Charles S. Ingalls as living

in Swampscott, MA. The Ingalls name was

prevalent in the area just north of

Boston ever since Edmund Ingalls founded Lynn, MA in 1629. Charles S. Ingalls, who died in 1894, was an

attorney and secretary of the New England Shoe and Leather Association. The records in the Swampscott Cemetery, however, do not list his children or his wife’s

name. Background material about Alfred Ingalls

indicates he lived in Lynn, MA, was related to the founders of the town, and was

also an attorney. If Alfred, who was

born in 1885, was related to Charles, then he could have been familiar

with Sorrento as a child and might

explain why he might have returned as an adult to buy Blueberry Lodge. It is

also possible that Alfred's wife Bessie (Mira Elizabeth Kimball Ingalls), whose maiden name was Kimball, was

related to J. Wesley Kimball, the mayor of Newton, MA who also owned land in

Sorrento in the early days.

In October 1938, a few years after buying Blueberry Lodge,

Alfred Ingalls also purchased lots numbered 17, 18, 19, 20, and 21 in Division

1, Section L from the Town of Sorrento, (see HCD book 664 / page 590). These are the same lots referenced on the later Hawley and Ridgely deeds. However, unlike those later purchases, the 1938 deed

makes no mention of any building existing on the land that was transferred to

the Ingalls with the sale. Given this, all indications are that the first structure on the land was assembled and erected by the Ingalls

during the ten years they owned the land between 1938 and 1948. Whether this first building was also a former motel unit brought in from another location is not known.

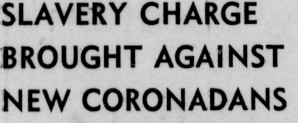

The Slave Quarters nickname that some later used to identify the house, can no doubt be traced back to the incredible and disturbing tale of Mr. and Mrs. Ingalls and Dora Jones. The first hint of the story is contained in the news stories in February 1947 from California about the arrest of the couple on the charges of "...involuntary servitude and slavery." Dora was also detained that night as a material witness and would later testify at their trial.

The couple's arrest had been preceded a few months earlier by another visit to a police station. During a cross-country

trip to California in 1946, it came to light that the couple had forced their

African-American servant to spend nights sleeping in their car. On October 11, 1946, the Ingalls' daughter,

Helen Ingalls Roberts, brought her parents' behavior to the attention of local

law enforcement when they visited her during a stop-over in Berkeley, California. Even after Bessie threatened Dora at the police station, the couple and their maid were permitted to leave without any charges filed. The Ingalls then continued their trip from

Berkeley to San Diego. The couple was building a new home there but it was not yet completed. During the month they waited for construction to finish, it was alleged they again made Dora sleep in the

family car parked on the street outside

of the famous Hotel del Coronado. Dora slept outside even though the hotel had rooms set aside for

servants and had no restrictions against African-Americans using those rooms.

The Ingalls's conduct was eventually brought to the attention

of federal authorities to determine if the civil rights of Dora Jones had been

violated. Following an FBI investigation,

the Ingalls were arrested in February of 1947 on charges of violating the constitutional

prohibition against slavery, and Dora was placed in protective custody. In March, a Grand Jury returned an

indictment charging the Ingalls with keeping Dora Jones in “illicit servitude.”

A sensational trial commenced later that

year in San Diego resulting in the conviction of Mrs. Ingalls. While Bessie may have been the first American since the late 1800s to be tried and convicted in the United States for keeping a slave, she was certainly not the last to exploit Black labor.

The incredible story of Dora Jones, the enslaved servant of the

Ingalls, began when Bessie -- then known as Mira Kimball and a recent college graduate -- began working in

rural Alabama as a teacher in her 20s. Bessie needed household help and engaged the assistance of then-teenaged Dora. When Bessie returned to Washington D.C. in 1907 to marry Walter Harmon and later had her first child, she was accompanied by her maid. Evidently, it was during this time that Dora was alleged to

have had an

affair with Bessie's husband, (or more likely raped), and became pregnant. Enraged at this deception, Bessie used physical

and psychological intimidation to have Dora terminate the pregnancy.

Following her own later miscarriage, Bessie divorced

Harmon and returned to Massachusetts with her first daughter and the obedient

Dora in tow. Bessie then married Alfred

Ingalls in 1917 and moved to Lynn, Massachusetts where the couple had a child of their

own. Dora worked for the family and helped to raise both girls. Bessie's second husband Alfred practiced law

and served in the state legislature.

During this entire period that Dora worked for Bessie and Alfred, prosecutors charged she did so without pay. It was also alleged that the couple inflicted both physical and emotional abuse on their servant and only allowed Dora to return home to Alabama a single time.

More of the unbelievable details of Dora Jones and the background of the Ingalls case was examined by genealogist Polly FitzGerald Kimmitt in her 2013 blog post, The Miserable Life of Miss Dora L. Jones, Latter Day Slave.

There was also an excellent 4-part series -- A SLAVE IN PARADISE -- written by historian Robert Fikes, Jr. in The San Diego Reader in 2017. Mr. Fikes provides additional background on the dysfunctional Ingalls family relationship, the trauma Dora endured as well as details about the Ingalls's arrest, trial, and verdict in California.

Bessie's cruel treatment of Dora over many decades eventually led her own daughter to report her mother's behavior to the police. The tragic story of Dora's years of involuntary servitude also extends into a larger drama within the Ingalls family and their two daughters who eventually found the courage to report the Ingalls to authorities. Reporting during the trial was covered widely by the press around the country and in African-American newspapers, such as the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Interestingly, one of the prosecutors in the trial was Betty Marshall Graydon, a trailblazing woman Assistant US Attorney in San Diego. During one dramatic day of testimony, Graydon put Dora on the stand and asked members of the jury to inspect her hands to decide whether “...they are the hands of a person who was a member of the family . . . or whether they are the hands of a slave.”

While the jury failed to convict Alfred Ingalls of the charges,

it did find Mrs. Ingalls -- despite her defense that Dora was simply her

“protégé” -- guilty of enslaving Dora Jones.

In the Summer of 1947, after a motion for a new trial was denied (see

US v. Ingalls), the

judge suspended Mrs. Ingalls's prison sentence. The judge however did impose a fine and ordered the couple to pay

Dora Jones $6,000 (more than $65,000 in today’s money) as restitution for her

40 years of involuntary servitude.

The background articles

and testimony offered during the trial

delve into the horrific details of the relationship between Dora Jones and the Ingalls but I could find no mention of Sorrento. We do know from the land records that twenty

years after the Ingalls were married, and when

their daughters were teenagers, they purchased Blueberry Lodge. We also know that two years later the Ingalls

bought several other lots overlooking the Back Wharf where they would erect a

second house.

Is it possible that the Ingalls bought the old Lamoine motel

buildings to erect on the property to provide Dora Jones sleeping quarters in

Sorrento, or was it instead built to give their daughters someplace to stay? Regardless, Dora, no doubt accompanied the family to Maine when they stayed in Sorrento.

As to the nickname the Slave Quarters, I can only hope

this name was not given to the house by the Ingalls. Despite their aberrant behavior, the Ingalls

vehemently denied the charges of keeping Dora in involuntary

servitude. Instead, I suspect this moniker was likely used in Sorrento only after the nationwide publicity surrounding the Ingalls’ sensational trial in California. What is not known is who began and perpetuated the use of this nickname, was it the summer vacationers, local Sorrento residents, or both? Thankfully, in recent decades this name has stopped being used.

Remarkably, the current owner of the house has what appears to be a carbon copy

of an undated letter that Alfred Ingalls wrote just before their federal arraignment in the spring

of 1947 in which he refers to his wife as “Bessie.” To whom he was writing is not revealed, but in it, he acknowledges the role his daughter Helen played in luring Dora away from her parents. It also confirms the battle within the family which led to their behavior first being brought to the attention of the

authorities, as well as details of the visit to the police station in

Berkeley. Notably, Ingalls argues that it was Dora who insisted on sleeping in the car and that their

arrest was simply the result of “...the Communist crowd...” attempting to “...stir up racial

strife.” Despite their arrest and upcoming trial, Alfred also indicates that the couple expected to travel back East in a few months and possibly even to Maine during what would have been

the summer of 1947.

By the time of their arrest and trial, the Ingalls had already sold

Blueberry Lodge in Sorrento to William and Leona

French of Cherryfield, ME. That deed transfer

was signed by the Ingalls in San Diego on November 15, 1946, (see HCD book 711

/ page 356), just weeks after their first encounter with police in Berkeley and

during the time they were staying in temporary quarters in San Diego with Dora. A few months later the couple would be arrested after the reports were verified that Dora was forced to sleep in their car or on the beach outside of the hotel and was not being paid.

We know from the Sorrento deed records that the Ingalls did not sell the little white house there to Mrs. Ridgely until July 1948, one year after the trial was over. If they were going to return to Sorrento in 1947,

as Ingalls indicates in his letter, then they would have only had the Slave

Quarters cottage in which to stay.

While conducting this research, I found one other interesting property

transfer the Ingalls made with another parcel

of land they owned in Gouldsboro. In November 1925, Bessie (Mira E. Ingalls) bought 65 acres of

land in Gouldsboro from Sarah A. Hill of Boston, (see HCD book 598 / page 150). This land just up the road from Sorrento was purchased by Mrs. Ingalls twenty

years before buying

Blueberry Lodge. Therefore, I suspect either Alfred or Bessie (Mira Ingalls) had family roots in

Down East Maine and had been summering in

the area before buying

Blueberry Lodge in 1935.

Local newspaper accounts indicate the Ingalls had a summer house in West Gouldsboro before moving over to Sorrento.

But there is one other disturbing twist revealed in the Ingalls Gouldsboro land records. On April 24, 1931, Bessie (Mira Ingalls) “sold and conveyed” 3,000 square feet of this property to Dora

Jones, (see HCD book 633 / Page 399).

Incredibly the very next day, April 25, 1931, deed records indicate that Dora

Jones transferred the land to Bessie's husband Alfred Ingalls, (see HCD book 633

/ Page 400).

In May of 1940, the Ingalls

established a Massachusetts corporation, Blueberry Lodge Inc., (see HCD book

672 / pages 346, 347 & 348), to hold all of their real estate

properties. Years before their arrest

and trial, their land in Gouldsboro along with the Sorrento

properties, were transferred to this holding company.

But the mystery remains as to

why Bessie (Mira Ingalls) sold this small parcel in Gouldsboro to Dora Jones and why the next day she transferred ownership back to Alfred Ingalls. Did the couple attempt to deceive

Dora as early as 1931 by providing her with a deed as proof that she was being compensated

for her labor? Or was there some sort of

tax advantage that the Ingalls were attempting to gain by using a sale to Dora as

an intermediary while eventually placing the property in the name of Alfred

Ingalls?

Regardless of the reason, this

seems like one additional sad postscript to this story, with Dora listed as the owner

of the plot in Gouldsboro for only 24 hours.

That illicit land transfer is not so surprising when reviewing the

accounts of the trial where it was revealed that Mr. Ingalls had used Dora’s

signature as a bondsman in a case in Boston in which he was named a guardian in the estate of a mentally

incapacitated person. There was further

testimony that Ingalls was alleged to have transferred stock from the account he controlled as

guardian to Dora’s name. Evidently,

Ingalls’ use of Dora as a surrogate to transfer assets was not unusual, but

there is no indication that the prosecutors continued to pursue this line of inquiry

against the Ingalls after the defense objected. As a lawyer,

however, this type of activity no doubt skirted ethical rules and could have

put Ingalls in even more serious legal peril. Evidently, Ingalls was able to stop any further investigations of his probable improper financial dealings.

After Bessie's conviction, being

denied a new trial and avoiding any jail time, the Ingalls remained in California

and eventually moved to Santa Barbara where they enjoyed a seemingly quiet

retirement. Alfred died in 1965 while "Bessie" (Mira) Elizabeth Kimball Ingalls would live until 1972, dying at the age of 87.

It appears, however, that neither Dora nor the Ingalls ever returned to Sorrento for another summer.

Dora Jones took the meager

$6,000 the court had awarded her for her forty years of psychological abuse and involuntary servitude and went to live with

relatives near St. Louis. Ironically she would die only two months before Bessie on March 1, 1972.

We may never know for certain if the Ingalls erected the

little white house overlooking the back bay for Dora to use when the family was

in Sorrento, or if it was built for their children or other guests. If it was used by Dora, then we might take consolation

that the nickname, despite its horrifying derivation, might be the result of a

time when people in town remembered a nameless African-American woman occupying the

house. By knowing and acknowledging this history of the Slave Quarters, I hope instead we will now associate the name Dora Jones when looking at the house.

One other mystery I ponder is whether Dora ever had any

interactions with Louise Morrell or Mother Katherine Drexel. These sisters had spent the bulk of their

fortune establishing schools and missions around the country to educate

African-American and Native-American children.

If Dora occupied the house just down the block, she probably walked past

the houses Louise owned innumerable times on her way to and from Blueberry

Lodge to work. If they had crossed

paths, and Dora had been able to make them aware of the many issues between herself

and the couple, perhaps an intervention might have occurred

much sooner.

Instead, Dora Jones continued to endure years of humiliation at the

hands of the Ingalls until their own daughter, at last, brought their conduct

to the attention of the authorities. Although

Dora never visited Sorrento on vacation, I imagine her sitting on the

porch of the cottage for a few relaxing moments at the end of a long workday. Perhaps Dora was even able to enjoy an occasional late evening summer sunset like so many others have been free to do in the decades since, and the chance to dream her own dreams.